In an era where modern forms of sovereignty are not merely concerned with the preservation of life but also with the management of death, the scope of the politicization of death has significantly broadened. Mbembe’s (2003) conceptualization of necropolitics articulates a form of sovereignty transcending the regulatory power of modern authority over life, centers on the sovereign’s capacity to delineate the conditions and modalities of death. This perspective reveals a structural regime of violence, particularly in conflict zones, wherein the state operates not only through the power to kill, but also through practices such as the exhibition of the dead, their abandonment without graves, the erasure of their identity, and their removal from collective memory.

In the four distinct regions inhabited by the Kurds,Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria,necropolitics operates not merely as an individual or sporadic form of violence, but as a continuous sovereignty strategy, illuminating the complex relationship between death, memory, and space.

In Mbembe’s (2003) work, necropolitics extends beyond the concept of biopolitics, emphasizing that sovereignty is grounded not in the regulation of life, but in the power to determine who will live and who will die. In this context, the modern state wields not only the right to kill, but also the power to determine the forms of death, legitimize certain deaths, and render others invisible. This concept is particularly useful in understanding multilayered processes such as the transformation of the body into a political object, the suppression of grief, and the instrumentalization of memory, especially within colonial and postcolonial contexts.

When applied to the Kurdish geography, necropolitics encompasses not only physical violence, but also the decision-making mechanisms regarding the fate of the body after death. This represents a multidimensional form of control, ranging from how the slain body is buried and whether its identity is recognized, to the accessibility of the grave and its place in public memory, thereby manifesting necropolitics in various forms. The practices of enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, mass graves, and the denial of access to funerals, which became widespread in Turkey’s eastern and southeastern regions during the 1990s, are connected not only to security policies but also to forms of intervention in memory. According to a 2014 report by the Human Rights Association, the remains of 4,201 individuals have been found in 348 mass graves identified solely in Bakur (North Kurdistan). These figures point to the existence of an institutionalized strategy aimed at erasing the dead body from the public sphere in Kurdish geography. The destruction of cemeteries, the vandalism of gravestones, the withholding of bodies from families, or their delivery via parcel post, are visible practices of these policies. In the ‘grave houses’ created by paramilitary groups affiliated with Hizbullah in the 1990s, it has been documented that civilians tortured to death were buried in the foundations of homes. Such structures create zones of social silence built upon the spatial arrangement of death, demonstrating that necropolitics is not only a physical but also a spatial strategy. This form of violence demonstrates historical continuity. In the late 1980s, Newala Qesaba (Butchers’ Stream) in Siirt became a site in Kurdish memory not only for the recent conflicts but also for traces of historical genocide. The region is known as one of the locations where many Armenians were mass murdered and buried during the Armenian Genocide of 1915. This historical layering transforms Newala Qesaba into not only a physical grave but also a memory space that reflects the spatial continuity of multiple regimes of repression. After the 1980s, this site regained a similar necropolitical function, becoming a place where PKK members who lost their lives in the conflicts and civilians who fell victim to extrajudicial killings were secretly buried. This dual history reveals that the grave is not only a marker of death but also a sign of the continuity of the state’s historical forms of violence. In this sense, Newala Qesaba functions as a ‘black hole,’ accumulating both physical bodies and suppressed collective memories, layering the state’s necropolitical strategies upon one another.

Similarly, the chemical attack carried out by Saddam Hussein’s regime in Halabja in 1988 clearly illustrates how necropolitical strategies intersect with ethno-political cleansing. The 2014 Sinjar massacre perpetrated by ISIS against the Yazidi people is another example of necropolitics, where the female body was systematically transformed into a tool of war.

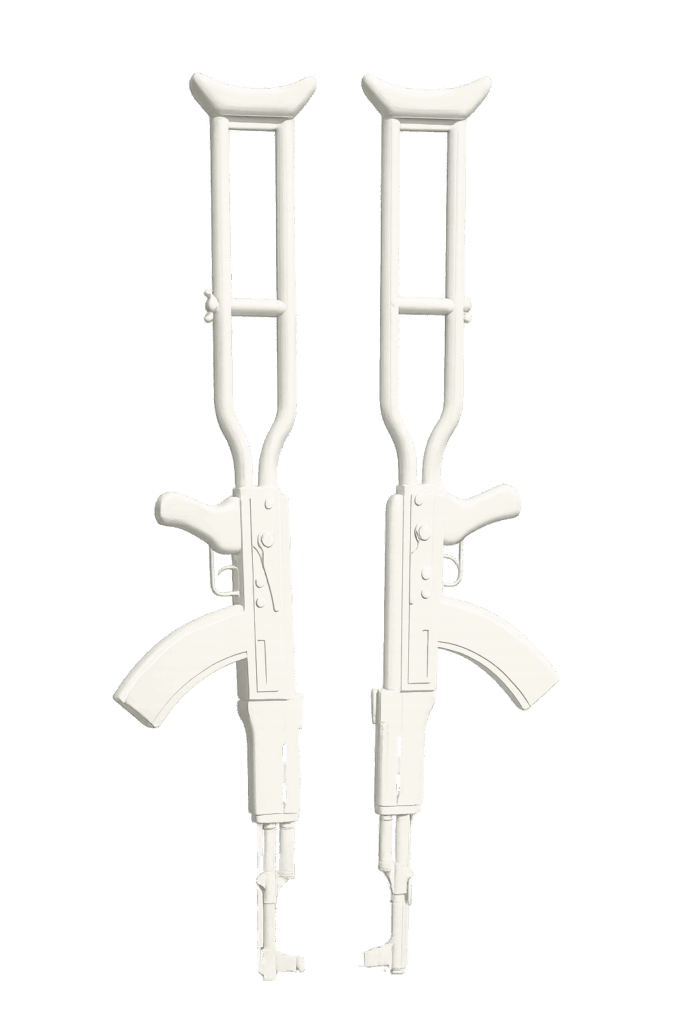

Against these structures, art can function not only as a representational practice but also as an epistemological site of intervention. Butler’s concept of the ‘right to mourn’ serves as a crucial reference point here. Whose deaths can be publicly mourned, and whose are silenced? This distinction is one of the most invisible yet most effective tools of necropolitics. In this context, art should not be seen as a mere representation, but as a practice of creating a counter-archive. The aim of art here is not to generate aesthetic experience, but to trace the traces of violence, question the invisibility of the perpetrator, and make visible what has been suppressed in public memory.

The works produced by Kurdish artists are particularly focused on spatial memory (cemeteries, depopulated villages), body politics (the display of corpses, dehumanization), and mourning practices (silence, public testimony). However, these productions should not adhere to classical aesthetic codes; instead, they should turn toward documentary, archival, and critical forms. This is not only an artistic choice but also an ethical and political one.

Against this regime of death, art should position itself not in beautification, abstraction, or neutralization, but in confrontation, subversion, and the construction of an alternative memory. In the face of unburied bodies, dehumanized corpses, and forgotten traumas, art should be regarded not merely as an aesthetic gesture, but as a space of political responsibility.

Therefore, in the Kurdish geography, art serves as a tool for preserving collective memory against necropolitics, reclaiming the right to mourn, and making the demand for justice visible. This tool gains its meaning not within the limits of representation, but at the threshold of resistance.

..